Eyes over instruments

In scuba training, one of the things they teach you is how to do is underwater navigation. This is generally harder than walking along the beach, because you have limited vision (especially at night), most sand looks pretty much the same, and you're primarily and rightfully focused on not breathing water. You learn how to hold a compass and flashlight steady, count your kicks, and adjust swim angle to account for current.

After successfully demonstrating that I could swim in a square, clockwise and counterclockwise, my instructor drilled into me when to ignore what I learned. Instruments can be used wrong. Your count can be off. The current may be stronger than you thought. Blindly following your instruments is an easy way to end up in a bad place. A compass doesn’t lie, but it might not be telling you what you think it’s telling you.

Instead, he said, the number one thing, if conditions allow, is to understand the dive site, visually keep track of true things, and navigate relative to them. If you're on the wrong side of the reef, it doesn't matter whether you counted correctly. The beach is always up the slope, and you can navigate by keeping it to your left or to your right. Bubbles always travel toward the surface. Fish and turtles and boats can move, but buoys and reefs and shipwrecks don't.

If you know you’re swimming between the beach and the reef, with the reef on your right, and you can see both, you don’t really need the compass.

In the modern world, though, it's increasingly easy to navigate the world through instruments and proxies. But they have a loose relationship with reality. Apple Maps used to send people to the Australian outback, and Google Maps tells you to take illegal left turns. Police and schools juke the stats. The teen depression crisis might be due to an Obamacare measurement change. A PowerPoint deck confidently tells you what a feature does, and whether it's in production.

This isn't to say that instruments are bad. It would be impossible to function in the world without them. But I try to treat them as what they are - proxies - rather than ground truth. And only measure things that you’re using to make decisions.

"The thing I have noticed is when the (customer) anecdotes and the data disagree, the anecdotes are usually right. There's something wrong with the way you are measuring it." - Jeff Bezos

I used to be really into sleep tracking. My watch, ring, and bed would give me rigorous quantitative evidence that I did not sleep well on Friday nights, supported by the anecdotal evidence of nausea, headache, and waking up on the floor1. By carefully logging ‘Drank alcohol’ into the apps, I could get a monthly email telling me how I could improve my sleep by drinking less. Measuring sleep in this case wasn’t wrong, but also was not very useful.

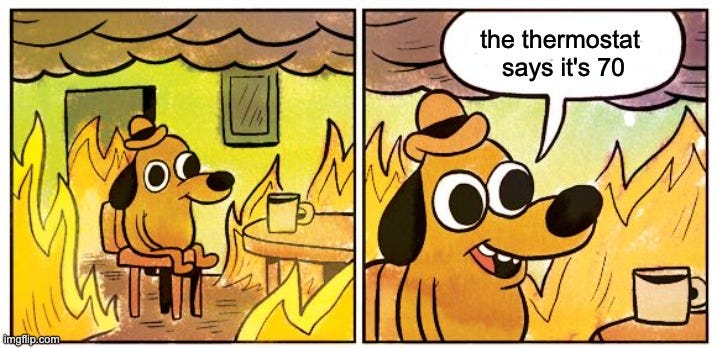

I would also sometimes wake up, feeling fine. I’d check the sleep tracker, and it would say that I didn’t get enough REM sleep or whatever, and I’d find it irresistible to conclude that I was going to have a bad day because I didn’t get enough REM sleep. So now I don’t measure sleep, drink less, and try to sleep around the same time every night, and it’s working out pretty well.

Treating proxies as proxies generally works well at the personal level, where you can look at a road sign and refuse to make an unprotected left across three lanes of traffic. You can try different foods and eat what makes you feel good, regardless of what your watch tells you. You can get your own oven thermometer.

Trusting eyes over instruments works less well at work, where you're often already dealing with abstractions of abstractions, everyone is performing for everyone else, and observing that the emperor has no clothes gets you executed.

One of my friends used to spend a lot of time on urgent fire drills from his CEO because one of the metrics was off forecast. He’d do a couple days of round the clock investigations before concluding that the DAU forecast was off because somebody hard coded Diwali last year. By itself, this isn’t necessarily the wrong thing to do. But the product that this was for hasn’t materially changed in the last 10 years, and the metric wasn’t being used to make decisions. My friend did get promoted.

It may not matter, for many values of 'mattering', that your metric is flawed and doesn't actually measure (e.g., likelihood a customer churns) - do you want to die on the hill campaigning to get it measured differently, or make number go up and get promoted? Usually it’s far outside your power to change it and your campaign will be viewed with suspicion.

I haven't got an answer for you. Maybe you can do both. Or neither.

But if you're looking for true inputs to make better decisions, I encourage you to look with your eyes rather than your instruments. Use the feature. Talk to a customer. Test your kid's algebra. Taste the soup. And steer clear of drivers who stare at their phones instead of the road.

Compliance would like me to remind you this is exaggerated for comic effect.